“New” is one of the strongest words in marketing. “New” invokes the belief that something is moving forward, that it is different, modern or improved. People are attracted to new products like a magnet. Introducing new products and services on a constant basis is the best way to get attention and is invaluable publicity for a business. “New” positions a company as being dynamic and forward looking. Companies such as 3M and Sony have held this slot for periods of time but it is difficult to stay there. In 2021, companies such as Apple and Samsung are at the forefront of bringing new products to market on a regular basis. Innovation is hard work and the road is paved with failures.

Introduction: The Importance Of “New”

This white paper shows how market research, when used correctly in product development research, will minimize the risk of failure. It also explains that market research does not always give a clear-cut answer – considerable insights and experience are required by the market research analyst to interpret the data and visualize the opportunity.

The word “new” is sometimes over-played in marketing because it is so frequently used for everything from conceptually new products through to old wine in new bottles. The main types of product development are as follows:

- New concepts – completely new products that have arisen as a result of innovation and which can sometimes create new markets.

- Additions to existing product lines – new products that supplement established product lines. For example, a supplier of industrial gases may introduce a new, smaller cylinder to include in an existing product line, aimed at serving customers who require smaller amounts of gas.

- Modifications of existing products – existing products that are modified in order to better meet customer needs, such as improved performance.

90% of new product research is focused on product ‘additions’ and ‘modifications’ rather than on the concepts. There is nothing wrong with this. Product improvements are obvious developments and are much more easily accepted than conceptually new products.

In fact, the more conceptually new the product, the riskier it can be. FedEx lost $340 million on its new Zap mail and DuPont lost an estimated $100 million on a new synthetic leather product called Corfam. With this in mind, many companies turn to disciplined market research as a form of insurance, i.e. as a means of reducing business risk. The next section looks at how market research is used in product development – not only as insurance, but also as a tool to establish needs and to obtain intelligence on market potential.

Product Development Research Across the Product Life Cycle

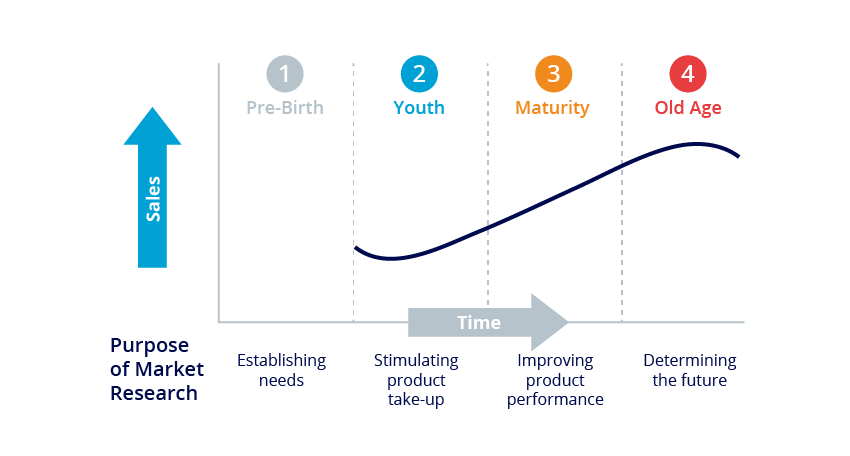

Product development research can be used at all stages in the product life cycle, as illustrated in Figure 1 and explained in the following sections on applications for market research.

Figure 1 – Applications For Market Research

Pre-Birth – Establishing Needs

Many companies recognize the importance of “new” and for this reason they allocate substantial sums to research and development. Electronics companies may have an R&D budget equal to 15% of their sales, but this is required in order to cope with the rapid pace of change in their sector. For most companies, the expenditure on R&D is somewhere between 2% and 5% of sales – still huge sums for the likes of Boeing, Honda or Siemens.

Over 90% of all innovations that are successful start in the wrong direction [ref 1], and are not the outcome of good market research. In fact, many new and successful products arise by accident and not as a result of hours and hours of focused R&D or significant financial investment. Indeed the telephone, X-rays, bubble gum, Velcro, Viagra and Post-it notes – to name but a few examples – were all invented by accident. In the case of Post-it notes, for instance, a researcher at 3M was eager to create the world’s best glue, but actually ended up creating one of the worst glues ever – one that didn’t stick – which nevertheless ended up as one of 3M’s most successful products: that of the ubiquitous Post-it notes.

Not all new products arise by accident, however, and product development research can play a role in determining the need for most new products. Drucker (1993) tells the story of William Conner, a medical salesman, who decided he wanted to set up his own company. Conner sought new product opportunities by visiting surgeons and asking them about the challenges they faced in their work. In these interviews, Conner learned that the process for cataract surgery involved a difficult task for physicians, in that they had to cut a ligament which was an unpleasant and risky move. Conner then discovered an enzyme which could dissolve this ligament (thus eliminating the requirement to cut the ligament), as well as a means through which the enzyme could be preserved until it was required in surgery. The innovation was a success, which led to Conner patenting his compound and meeting an unmet need in the industry – all thanks to market research which played an instrumental role in discovering and unleashing the market opportunity.

In the case of the cataract surgery, market research provided invaluable insights into unmet needs and a thorough understanding of the environment in which the new product would be sold. However, caution should be taken in terms of the expectations of market research, for it cannot be assumed that conducting research with the market will uncover sizeable opportunities and lead to the conception and launch of new products. It is the role and responsibility of the researcher to use the understanding of the needs of the market to find applications for new products that will satisfy these needs. The market cannot be expected to announce what the new product should be, and market research respondents cannot play the role of R&D Director!

Furthermore, it cannot be assumed that market research is an exact science, as it would be unrealistic and unreasonable to expect market researchers to predict the precise demand for a new concept, given that there are numerous variables that can impact demand outside of the market researchers’ remit. It takes years to get a product to the commercialization stage, let alone to get it well established in a marketplace.

Market research should be regarded as an experiment which may fail if it is not conducted in the right conditions. For example, Xerox commissioned three independent consultants to explore the opportunity for a copier. Two consultants advised against the launch and the third consultant forecast sales of 8,000 units over 6 years. Xerox chose to ignore the recommendations of the consultants, launched the copier and installed 80,000 machines within just 3 years. The market research had underestimated demand as respondents were unable to provide their views on a new product that they had never experienced.

Indeed, innovations that require potential users to try something new (which is likely to involve a change in mental attitudes) are difficult to research, given that potential buyers or users – when asked in an interview or focus group – cannot be expected to imagine using a product and to then state how likely they would be to buy it, or to state how much they would pay for it, without sufficient time to fully consider the product, or possibly trial it in the environment in which the product would be used. Imagine asking people prior to the launch of the Sony Walkman what they thought of the concept of a transportable music player that they could listen to on the move. Since people would have difficulty conceiving the notion, it could have received the thumbs down.

Nevertheless, market research can explore the underlying needs of the market and make a judgement as to how well a new product meets these needs. Hence it is the researcher, and not necessarily the potential buyer or user, who makes the connection between the unmet needs and the new product development opportunities.

Key questions that should be asked in any concept screening research include the following:

- Is the purpose of the concept clear and can potential users be persuaded of the product’s benefits? (This will show the clarity and purpose of the offering.)

- Does the product meet a need? What is the specific nature of potential users’ requirements? (This will assess the demand for the product.)

- How are existing products used, i.e. for how long, how frequently, precisely what for etc.? (This will show the behavior of people buying existing products.)

- What challenges do people face in using existing products and what requirements are not being met? To what extent are users of current products satisfied with these products and their suppliers? (This will identify any gaps in the market.)

- Is the price reasonable in light of the concept’s perceived benefits? (This will show if people are prepared to pay an appropriate price for the new product.)

- How likely are potential users to buy the product? (This will show purchase intent, i.e. how many people are likely to buy the new product – at least at face value as this will certainly be affected by the promotional push.)

Companies can be guilty of claiming they already know all the answers. This appeared to be the case with Sony, which had not conducted enough market research prior to commercializing its e-Villa Internet appliance. This new product was intended to enable consumers to have internet access from their kitchens, but the product failed as it was simply too heavy to lift at nearly 32 pounds and 16 inches. Consequently, the product was withdrawn after just three months. However, had Sony conducted more market research, it could have potentially saved a considerable amount of money in terms of the financial and human resources that were required in the product development and commercialization process.

A further point to consider in the pre-birth stage is that it is not just the product that needs to be right prior to commercialization; it is everything surrounding the product, such as the packaging, services (e.g. technical service) and marketing. The design, coordination and commercialization of all of these aspects can take many years, especially in the case of industrial innovations, which have been known to take decades. Carbon fibers, for instance, were discovered in 1965 and produced in the 1970s, but it was 20 years until they had a significant impact. Indeed it takes time for people to not only learn about a new product, but to be persuaded about the product’s benefits and to use it.

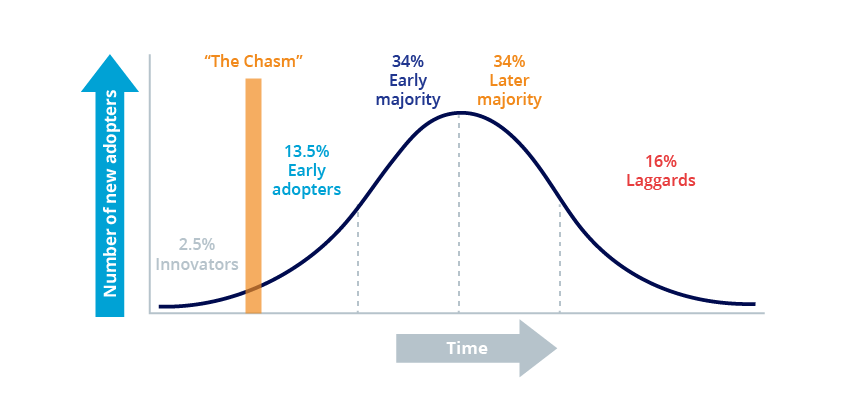

The innovation adoption curve (Rogers, 1995) illustrated in Figure 2 shows the change in the number of new adopters of a product over time, at different stages of the product lifecycle. The innovators are the earliest users of the product who welcome change, followed by the early adopters who are also willing to try new ideas but who tend to be more conservative. The early majority then take up the new product (and accept the change sooner than the average), followed by the sceptical, later majority which will use new ideas or products only when the majority is doing so. Finally, the traditionalist laggards are critical of new ideas and tend to only accept new products once they are mainstream.

Figure 2 – The Innovation Adoption Curve (Rogers)

In order to penetrate a market and achieve adoption, it is vital to educate the market about the product. It is necessary to jump “the chasm” and find sufficient momentum to take the innovation forward. For example, the largest wine producer in the world, E&J Gallo Winery, once sought to introduce a new wine-based drink to the market, which would be mixed with an ingredient to keep the alcohol content down below 5%. At the time of the conception, it was uncertain as to what ingredient this would be, but it was anticipated that it could be sparkling water, tonic or fruit juice. Market research costing in excess of $100,000 (a huge sum at the time) was conducted and led to an extremely clear result: consumers hated the product as they assumed that it contained the worst quality wine and they couldn’t really understand the purpose of diluting a fine wine with water or something else. This inability to communicate the benefits of the new product put the wine drink in jeopardy.

Not only did E&J Gallo fail; it was also humiliated as the concept was being worked on at the same time elsewhere by two young men who believed they had understood the changing market and people’s (especially women’s) interest in a lighter, less alcoholic drink. They developed a bottled “spritzer” product that was almost the same as the one that E&J Gallo’s research had claimed would bomb. On a shoe string budget they launched their product in California and soon it was a multi-million dollar business that they very shortly sold to US distiller Brown Foreman. E&J Gallo made the mistake of thinking that market research would give them a green or red light on their conceptually new product, rather than help them understand if there was an unmet need that they could stratify in some way.

In summary, the most effective types of market research studies for product development at this stage of the life cycle are needs assessment research studies (in which the usage of existing products are examined and unmet needs are explored), and concept screening (in which a new concept can be shown to the target audience for feedback on the product, but only if the product is presented to the users properly and if they are given sufficient time to understand the product’s benefits).

Youth – Stimulating Product Take-Up

In getting a product off the ground, there are three crucial questions that need to be answered:

- Where does the product/company stand at this point in time?

- Where does it wish to go?

- How can it achieve its goals?

Market research is highly effective in providing answers to all of these questions through product development research. It can provide an assessment of the size of the market, its growth prospects, the distribution routes, the market segments, and factors influencing the purchasing decision, plus suppliers used and their perceived strengths and weaknesses. It can guide product design, price points, packaging design, promotions and service (i.e. all elements of the marketing mix).

Some companies conduct market research in-house to answer these questions, but this can result in internal, political conflict, and can end up delaying the adoption of the new product. Using an independent market research supplier will speed up the process and, as Kotler and Keller (2006) argue, “Being early can pay off”, so much so that research has revealed how “products that came out six months late – but on budget – earned an average of 33% less profit in their first five years, [whereas] products that came out on time but 50% over budget cut their profits by only 4%”.

In summary, typical market research studies conducted at this stage of the product life cycle include needs assessment research (or market opportunity research), b2b pricing strategy research and ad testing market research or communications testing.

Maturity – Improving Product Performance

The applications for market research at this stage of the product life cycle echo the applications appropriate for earlier stages in the life cycle. For instance, market research can be used here for exploring optimum price points, for determining market share and market size, and for gauging attitudes towards the consumption of the product. In addition, views on the product in question can be compared to the perceived strengths and weaknesses of competitors’ offerings used, and along with unmet needs, the research can uncover potential product development opportunities even at this stage of the product life cycle.

It is vital not to neglect products at this stage in the life cycle, for continual product improvement is required in order to retain customer satisfaction. Most companies lose 45% to 50% of their customers every five years, and winning new customers can be up to 20 times more expensive than retaining existing customers. Product development research indicates to customers not only that a company is listening to the market’s needs, but seeking to respond to these needs and to improve its offering.

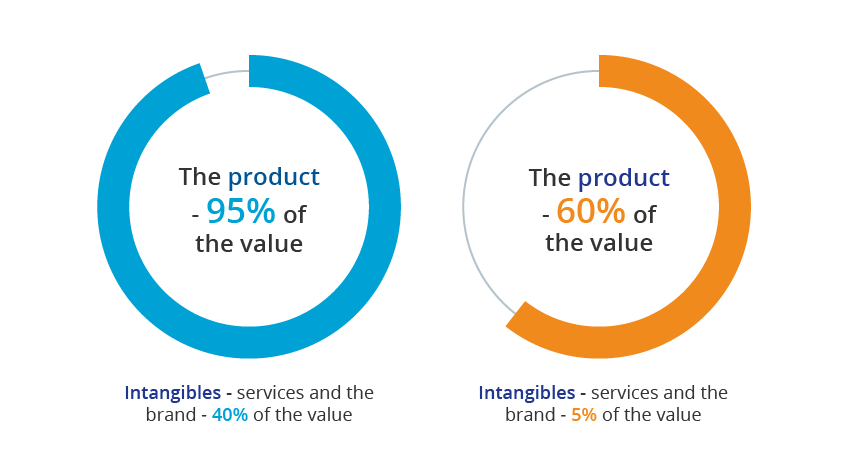

For example, a supplier of office furniture, “Supplier X”, could be regarded as just an average supplier in an industry in which all manufacturers’ products are viewed as similar. In this case, Supplier X’s furniture – the product – comprises 95% of the value, as illustrated in the left diagram in Figure 3 overleaf. If market research were conducted and revealed that companies purchasing office furniture actually had specific unmet needs around the product, such as the ability to customize furniture, assistance with interior design and delivery of furniture after 5pm, then Supplier X would need to build value around other parts of its offering, as illustrated in the right diagram in Figure 3. Thus by researching the product in its widest context, market research can be instrumental in rejuvenating a product, even at this late stage of its life cycle.

Figure 3 – Improving The Customer Value Proposition

In summary, typical market research studies conducted at this mature stage of the product life cycle include customer satisfaction research (in order to retain existing customers and hopefully attract potential customers), b2b market segmentation research (to determine how to tailor an offering to meet the needs of different segments) and pricing strategy research (to determine optimal price points so as to achieve maximum profits).

Old Age – Determining The Future

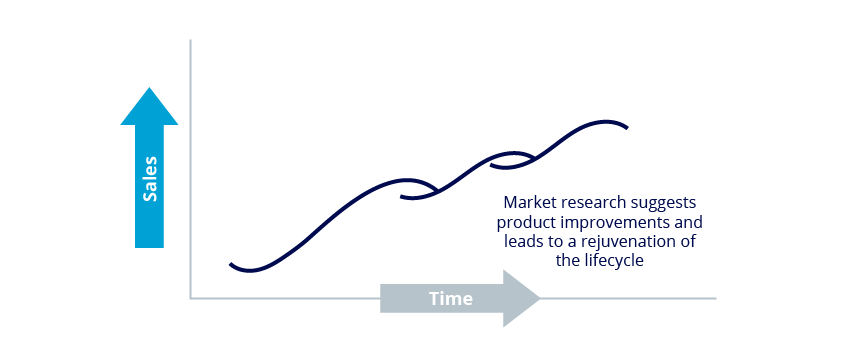

The final stage in a product’s life cycle comprises the product’s decline, with substitutes (often cheaper or more efficient) and new innovations gradually eclipsing the product as its sales wane and its profits are squeezed. Not all products necessarily die though as there are often opportunities for modifications and improvements which can result in a rejuvenation of the life cycle, as illustrated in Figure 4. Such opportunities for revitalizing a product can be uncovered through product development research.

Figure 4 – Rejuvenation Of The Product Life Cycle (Hague 2002)

Market research can help a company seek new markets for its aging products. Car plants have been sold by Fiat and Renault to Russia and China to produce models that are perfectly acceptable in these developing markets but which were seen as out-dated at home. Companies making ski poles and hitting mature and static markets can find new outlets by developing new products such as walking poles.

In summary, typical market research studies conducted at this aging stage of the product life cycle include needs-based assessment studies (in order to determine any unmet needs and to uncover potential product development opportunities), and market assessment studies (to gather market intelligence and to determine market potential in a new or an export market).

Determining The Type Of Market Research Required

New product development research almost certainly will require a mixture of qualitative and quantitative research.

Qualitative research is necessary to obtain a deep understanding of issues such as requirements and unmet needs. It allows more freedom in exploration depending on respondents’ areas of interest. The principal research tools of qualitative research are focus groups or depth interviews, which allow questioning and probing far below the skin of the subject.

Once the needs have been understood and it is clear that there is a market for a new product, some means is required of measuring the size of demand, usage habits, attitudes to products and the likelihood of up-take of the new product. Quantitative research now takes over and a relatively large number of structured interviews are required to provide a robust and statistically valid result. Such quantitative research studies tend to be conducted either by telephone or online.

Market research can cost anything from $20,000 (for a couple of focus groups, for example) to $150,000 or more (for a wide ranging study incorporating focus groups and quantitative research).

Example Of Product Development Research In Action

Envirotainer are the global market leader in secure cold chain solutions for air transport of pharmaceuticals. To remain at the forefront of innovation, they approached B2B International to help understand how they could differentiate a new container solution in the market based on customer needs.

Envirotainer wanted to understand which features of the new container would be most important to customers and how this would affect their willingness to pay. They also wanted to gain an understanding on which features to prioritize in their marketing once it was ready to take to market.

To read in detail how multiple types of primary research, including customer journey mapping workshops, in-depth interviews and a large-scale quantitative survey were used to develop and successfully launch the new container solution, check out the full case study.

Conclusion

Product development research is used at all stages of the product life cycle, from the conceptual stage through to maturity. It serves a host of purposes, such as establishing (unmet) needs, estimating likely demand, setting prices, shaping the specification of the product or determining optimal price points, to name but a few examples. What’s more, market research can unleash potential opportunities for new products, as well as rejuvenate existing products, perhaps by incorporating new features or finding new markets. Given the costs involved in innovation, research and development, and commercialization, as well as the costs incurred in maintaining an aging weak product, product development research provides a high return on investment.

This paper has shown that product development research does not just examine the product alone; it explores everything surrounding the product such as packaging, service, brand and company reputation. Product research should encompass the whole customer value proposition, and improvements to packaging, delivery, or any aspect of service support could have just as big an impact as improvements to the physical product itself.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that people’s tastes change slowly; they gradually see and acknowledge the adoption of products by others; and over time they are influenced by regular exposure to promotions. An initial rejection of a new product in a market research study may shortly become an enthusiastic embrace as attitudes change. Hence market research cannot be expected to give definitive and direct answers to new product questions; rather it should be used to provide a backdrop of understanding to the needs and unmet needs of the market. It is the researcher’s task to use these insights in order to assess the new product’s potential. New product research needs more intuition and judgment from the researcher than any other tool in the market researcher’s tool kit.

Bibliography

DRUCKER, P.F (1993)

Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Collins

HAGUE, P (2002)

Market Research. (3rd Edition) Kogan Page

KOTLER, P (1999)

Marketing Management: Millennium Edition. (10th Edition) Prentice Hall

KOTLER, P., KELLER K.L. (2006)

Marketing Management 12e. Pearson Prentice Hall

LEVITT, T (1969)

The Marketing Mode. New York: McGraw-Hill

ROGERS, E.M (1995)

Diffusion Of Innovations. (4th Edition) New York: The Free Press

Other References

Readers of this white paper also viewed:

Product Strategy: Act Your Age Product Development: What You Want, Baby I Got It Getting Concept Testing Right