It’s fair to say that my obsession with the Olympic Games began with Atlanta ’96. Whether it was Muhammad Ali lighting the torch at the opening ceremony, Linford Christie being disqualified as reigning men’s 100m champion, or Steve Redgrave giving us his permission to shoot him after winning gold in the coxless pairs (Team GB’s only gold medal in those Games, would you believe) – frankly it didn’t matter. It was sport. Sport at the highest level. And plenty of it – wall-to-wall coverage for two weeks, even in the days before red buttons and streaming. I couldn’t get enough of it.

As a young whippersnapper of only seven years, I suppose I could be forgiven at the time for having Olympic aspirations of my own. I genuinely believed that if I dedicated myself to the task, I could become an Olympian one day. The following year, I even went as far as to organize a street Olympics in my neighborhood. Cue memories of me marking out an 8-lane running track with chalk, and launching a makeshift javelin fashioned from a plastic pole down the road, to the absolute horror of approaching cars.

In the years since, my enjoyment of the Olympics hasn’t waned, but the possibility that I’d make it onto the podium myself sadly has. I’ve had a lot of fun over the last month chatting with friends and colleagues alike about which Olympic sport we’d be best suited to or would be easiest to take on (watch out, 20km race walk!). But in all seriousness – and I’m stating the obvious here – Team GB isn’t going to come calling. Nor is Team Ireland. And I don’t have any grandparents from the Solomon Islands.

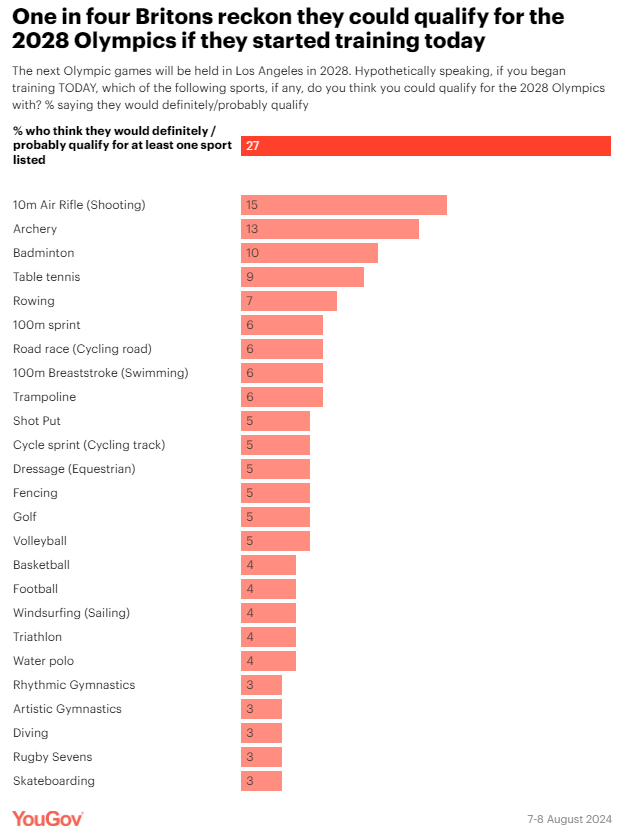

I was therefore extremely surprised to read about a recent YouGov poll in which 27% – more than 1 in four – Britons surveyed (using a sample of n=2,070), suggested that they would either “definitely” or “probably” qualify for at least one sport in the 2028 Olympics in L.A.

Can we just stew on that for a second?

Do a quarter of Britons really, truly believe this? Putting aside those fun chats at the dinner table or by the water cooler or in weekly Teams chats, just how overconfident / uninformed / unserious are we?!

After having glanced at the headline from the poll, I thought of a few reasons why this might happen:

-

People have a tendency to grossly overestimate their own abilities (does anyone remember another YouGov poll from 2021 in which 10% of Britons surveyed felt they could beat a chimpanzee in a fight if they were unarmed?)

-

People don’t understand the level of skill required to compete in a sport about which they might know very little (“it’s just aiming a bow and arrow at a target; how hard could it be?!”)

-

People don’t take survey questions like this seriously / data reliability to hypothetical survey questions is always problematic

-

The survey question was designed in such a way as to produce (dare I say, intentionally?) an attention-grabbing result

All four of the above may be contributing to the result here. But I’d like to focus on the last point – the idea that survey question design could have influenced how people responded – and how the results were analyzed.

For starters, let’s look at the exact way in which the question was phrased:

“The next Olympic games will be held in Los Angeles in 2028. Hypothetically speaking, if you began training TODAY, which of the following sports, if any, do you think you could qualify for the 2028 Olympics with?

The scale used was as follows:

- Would definitely qualify

- Would probably qualify

- Would probably not qualify

- Would definitely not quality

- Don’t know

Respondents were shown a list of 25 Olympic events/sports and were asked to provide a rating for each.

And here’s the rub: any respondent who selected “definitely” or “probably” for any of the 25 events, were counted in that 27% headline figure.

Source: YouGov

The issue I have with the question – as a market researcher and a dad of two in his mid-thirties grieving the loss of his own Olympic dream – is that with such a long list, the likelihood of a respondent selecting at least one event was always going to be artificially high.

Why is that?

Well, this is where the anchoring effect comes in.

The anchoring effect is a cognitive bias or heuristic – first theorized by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the 1970s – that causes us to rely heavily on the first piece of information we receive or provide (the “anchor”). We tend to base all subsequent information (again, whether we’re receiving or providing that information) on that anchor. In other words, our responses and decisions are made relative to something else, rather than being based in absolute terms.

In survey research, we typically see this effect when respondents see large grids of attributes in the same question. And sometimes, having an anchoring effect isn’t necessarily a bad thing. For example, if we want to understand levels of satisfaction with a supplier on a variety of touchpoints, a respondent “anchoring” themselves on the first attribute is acceptable, as we want them to think about a supplier’s performance in certain areas relative to others. We can mitigate the effect on the overall results by randomizing the order of the attributes.

However, in the case of our Olympic hopefuls, the anchoring effect has produced elevated levels of confidence.

Imagine reading the first of the 25 events. Let’s say that it’s diving. “There’s no way in the world that I could qualify for the Olympics in diving. I get vertigo stepping out of bed in the morning, let alone a 10-metre platform.” So, you select “would definitely not qualify.” You move on, feeling a tad inadequate.

The next option is 100m breaststroke (swimming). You think, “well, I’m better at swimming than I am at diving! Especially if I’m allowed to bring my armbands.” So, you select “would probably not qualify.”

The next option is 10m air rifle (shooting). Now we’re talking. Even though you’ve never held an air rifle in your life and you don’t know how far away 10 meters is, you did just see that Turkish chap win a silver medal without wearing any goggles or ear protectors. “I wouldn’t need to get in as good shape as the swimmers or the divers. This is the one for me.” “Would probably qualify.”

And there you have it. You’re now one of the 27% of Britons who think they’ll be strutting down the red carpet in Tinseltown in four years. Get the flights booked now because apparently, 18 million others will be joining you.

As soon as respondents have the “anchor” in their mind, all other responses they provide are essentially relative to what has come before. And with such a long list of events, the risk of an inflated result was always there.

It’s worth noting that this question is not measuring the actual likelihood of ordinary people like you and me qualifying for the Olympics. What YouGov is measuring here is perceived likelihood – or put another way, the level of confidence we have in ourselves.

But that doesn’t mean we can accept any old answer, no matter how ridiculous. Perhaps it’s impossible to ask a question like this in a survey because people simply won’t take it seriously.

But, assuming for a second that they will – I still don’t think that 15% of people surveyed believe they would definitely or probably qualify for the 10m air rifle competition. I just think that they believe they’re more likely to qualify for the 10m air rifle than they are to qualify for the diving. It’s likelihood in relative terms, not absolute terms.

So, if we really have to ask this question, what would have been a better way to do it?

-

Ask one question up front: “If you began training today, how likely is it that you would qualify for a sport/event at the 2028 Olympics?” Anyone selecting “definitely” or “probably” is asked to specify (open-ended) which sport(s)/event(s) they would qualify for. This eliminates the anchoring effect but it still probably produces an inflated result as people are being asked to think about their likelihood of qualifying for any sport.

-

Show each respondent one random sport from the list: “If you began training today, how likely is it that you would qualify for the shot put at the 2028 Olympics?” This also eliminates anchoring effect but is also specific enough that people are likely to think more carefully about their response. However, sample robustness becomes an issue as our 2,000 survey respondents now produce only 80 data points per event. Not great if you want to know what % of over 65s think they are the next Usain Bolt (I kid you not, 2% – according to YouGov’s cross-tabs).

-

Change the scale: Half of the answer options in YouGov’s survey indicate a reasonable likelihood – extremely disproportionate to the reality of the scenario being posed. What if we had more options and they related to perceived future skill level. For example, “If you began training today in the following events, what skill level would you attain after four years (i.e. in 2028)?” The response options could range from “Below average for my age group” to “Olympic standard” with plenty of detail in between. The likelihood that someone selects the very top option is surely less likely, even if the survey results may still reveal a degree of overconfidence.

All that said, maybe I’m just being a buzzkill. Maybe it’s ok that we think 1 in 4 of us think we could be Olympians. Maybe it means we’ll wiggle our hips more when we go out for a walk or face our fears and jump off the high-board. Or maybe we’re right to be confident in our sporting abilities, in which case Steve Redgrave should be concerned about our aim…!

Readers of this article also viewed:

B2B Insights Podcast #61: How to Ensure B2B Market Research is Strategic and Actionable B2B Insights Podcast #62: How to Achieve World-Class Quality in B2B Market Research Transforming Tradition: Embracing Innovation in B2B Research When to Use Qualitative Research to Better Understand Your Customers and Their Needs How to Ensure Representativeness of Samples in Customer Research The Importance of Compliance and Data Protection in Market Research Unlocking Deeper Insights with AI Probing in Online Surveys